Design Researchers in Residence is Future Observatory’s programme for design researchers hosted at the Design Museum.

James Peplow Powell is one of four Design Researchers in Residence currently working on projects responding to the climate crisis under the theme of Islands. Ahead of the opening of the researchers’ exhibition at the Design Museum in late-June, our coordinator Leilah Hirson-Comley caught up with James to learn more about his work.

LHC

Could you introduce yourself, and your research project?

JPP

I am an architect with a research-led “multispecies design” practice. Multispecies design means not only designing with people in mind, but also the many other forms of life which humans cohabit with and depend upon: animals, plants, fungi, microbes, and the relationships between them.

My current work is engaged with this practice of multispecies design on some new building and retrofit projects in my own design studio, as well as public art, exhibitions, and education with my research collective Feral Partnerships. It’s an ongoing experiment in what it means to practice architecture responsibly and ethically in a time of climate and ecological breakdown.

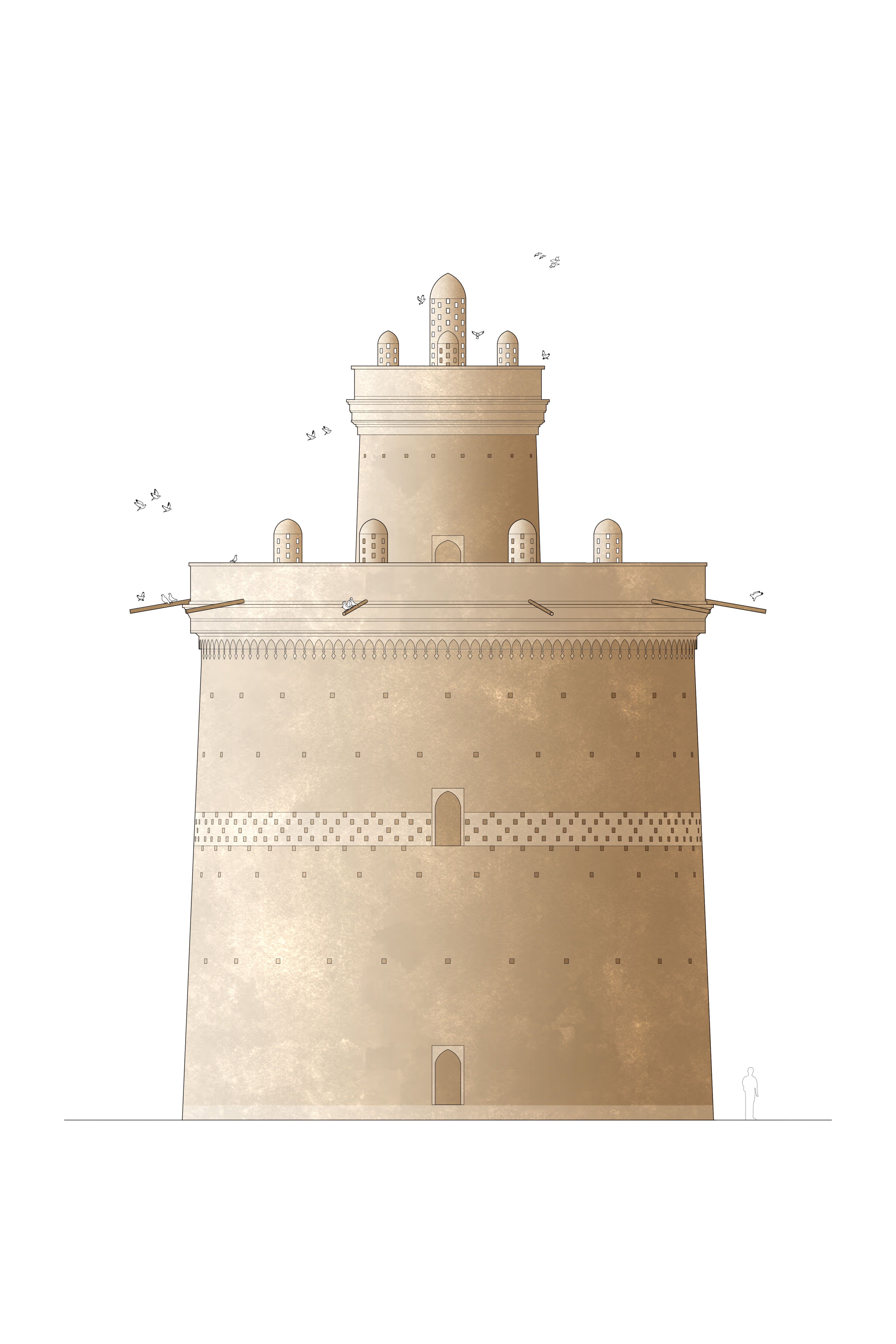

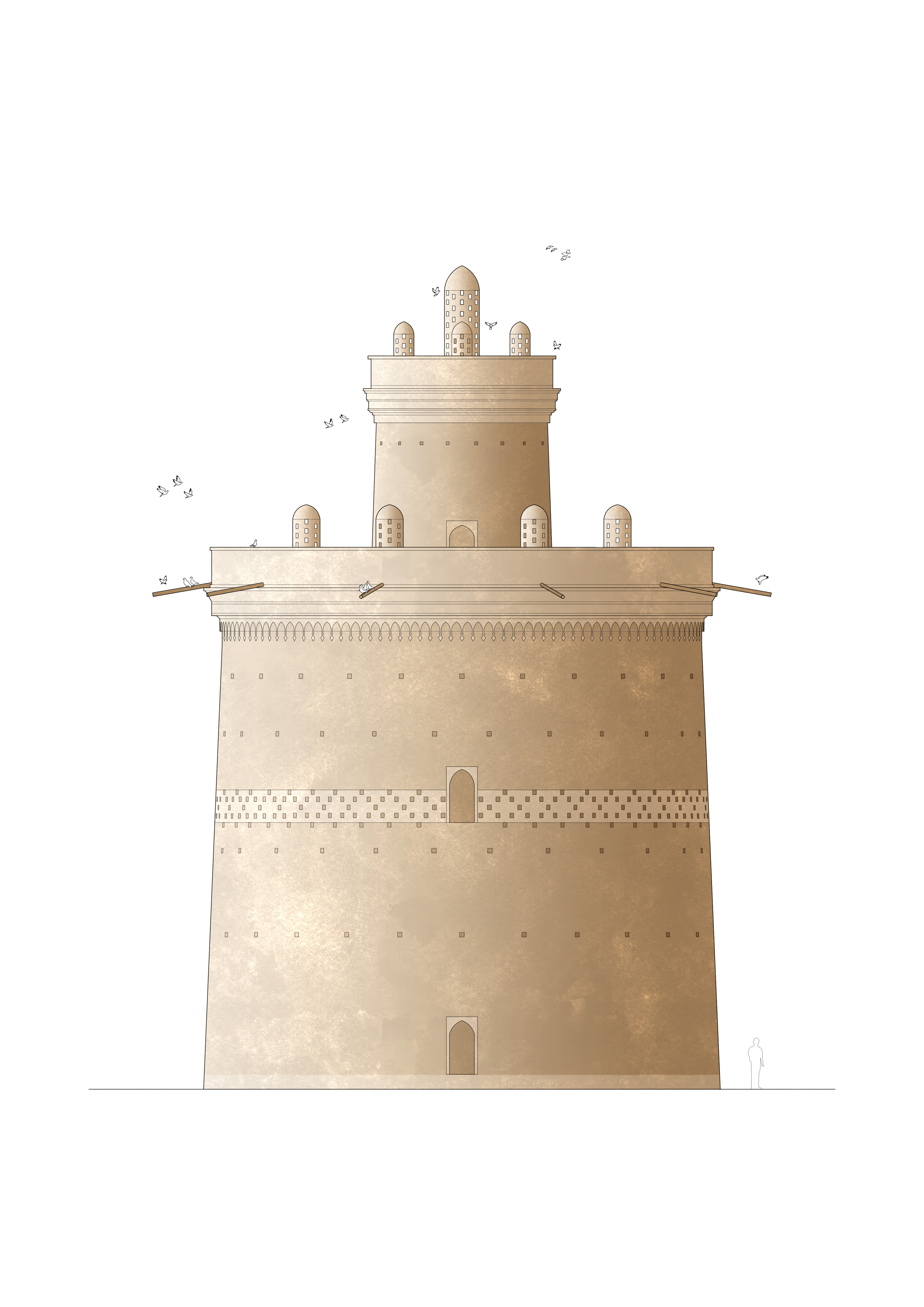

The working title for my project is “Dove Love” and it argues that, if we care about the planet, we should care about pigeons. I started out with an interest in the architectural typology of the pigeon house or dovecote, with a focus on the numerous and elaborate examples on the island of Tinos, Greece. I’ve since come to focus on our relationships with pigeons here in London, and how we might re-think our cohabitation with them with an understanding of our much longer, closer, and more productive histories together.

LHC

Why is the relationship between humans and other species important for tackling the climate crisis?

JPP

The importance might not be immediately obvious, because we tend to think of our relationship with other species through the lens of practices such as conservation or agriculture. Species are divided into ‘domesticated’, where our relationship is often seen as actively bad for the climate and for biodiversity, or ‘wild’, which are worth saving in island reserves but not seen as relevant to ‘human’ problems like climate change. There isn’t much awareness for human relationships with other species that might sit outside of those binaries.

This is changing though: for example, it is increasingly well known now that the Amazon rainforest is worth preserving not just for its biodiversity, but because of the work it does for regulating our climate, absorbing carbon dioxide and emitting oxygen. It is perhaps less well known that the Amazon has not always been a wilderness, but was densely inhabited and tended to by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. This introduces the idea of human care for nature, such as this indigenous agroforestry, as a critical infrastructure for planetary health.

My research has been finding that this isn’t only the case for great, glamorous, exotic examples like the Amazon, but for the humble, everyday and close-to-home. The pigeon is an archetypical example. The dovecote, employed not just in Tinos but across the Mediterranean, the Middle East and North Africa, is primarily an environmental infrastructure. Pigeon guano (shit) was once considered to be the best fertiliser around, and its collection at dovecotes was critical to making otherwise infertile places cultivable.

These sustainable, decarbonised sources of fertiliser were abandoned over the 20th century when fertiliser production became synthesised with the Haber-Bosch Process. This has been an environmental disaster, producing 450 million tons of CO2 annually, while excessive run-off has formed enormous aquatic dead zones in rivers and seas. We tend to think of this enormous environmental damage as a problem that can be fixed by more and better technology, rather than linking this to the demise of ancient and regenerative human-pigeon relationships.

To me, this is a positive discovery, because it means that the partners for a sustainable future don’t need to be invented. They are all around us, unused, and waiting.

LHC

What can we expect to see in your display at the Design Museum?

JPP

A dovecote for London! The city’s huge and generally vilified pigeon population is also the reminder of an obsolescent infrastructure. These pigeons are the descendants of homing pigeons, bred for purposes such as communications, as well as domestic companion animals. You can see design for pigeons almost anywhere in the city, and particularly around key public spaces, sites of urban regeneration, and transport infrastructure. These designs – spikes, netting, etc. – aim to exclude pigeons' remaining presence in our cities.

My prototype dovecote aims to be a more effective management tool by accepting and designing for their cohabitation with us. In doing so, it opens up opportunities to care for pigeon welfare, and to offer a regular supply of guano as high-quality fertiliser for London’s emerging urban farming network. To make the proposal work, I am thinking through unusual design problems such as: what makes an attractive architecture to pigeons? How might guano be captured most effectively?

This proposal will be shown alongside archival objects, images and drawings that give a window into the long history of human-pigeon cohabitation and our partnerships with them.

LHC

Where do you hope to take your research next?

JPP

My proposal for the dovecote for London is speculative but grounded, and I’d like to make it a reality, whether that is in 2, 5 or 10 years. The house for pigeons is something that has precedent in Europe, and is being currently rolled out in Paris, though there as elsewhere it is being implemented purely as a method of controlling pigeon populations. Here, the collection of guano, if proven practicable, should help with institutional sustainability targets, as well as potentially allowing the dovecote to pay for itself. I am approaching stakeholders in the city who deal with the presence of pigeons, such as Transport for London, to see whether the research is of interest.

Design Researchers in Residence: Islands opens at the Design Museum on 23 June 2023.