Ahead of the opening of the exhibition Design Researchers in Residence: Islands at the Design Museum later this month, we’re sharing a preview of the accompanying exhibition catalogue. The following conversation sees Future Observatory’s curatorial director, Cher Potter, in discussion with the 2022/23 cohort of Design Researchers in Residence on the topic of design research.

CP

Depending on who you ask, design is an aesthetic tool, a business strategy, a problem-solving technique, a cultural influencer, a critical mindset. If design itself is understood so broadly, how do you understand design research?

JPP

For me, design research is deliberately polyvalent. It synthesises lots of different concepts. As a group, we’re focused on biodiversity and the climate and how these issues are interrelated and critical to our time. I use design research to unpick and analyse the structures we’re using to think about these issues in more technical or systemic ways. Design research can synthesise ideas across disciplines and pose new questions.

RD

Design research can also help build a framework or a manifesto so that as a designer you can situate yourself within the context of existing ecological, social and political projects.

You can’t put forward any kind of design proposition without understanding the context you’re operating in, which is where research really plays a role. You immerse yourself in the work of other players, key stakeholders, their perspectives, pedagogies and knowledge systems to work out where, as a designer, your agency lies within this larger context.

IL

Your position as a designer adds something, you become a facilitator for cross-disciplinary thinking.

CP

So on the one hand the design researcher builds cross-disciplinary frameworks for design practice; on the other hand, they support different groups to exchange ideas and generate shared ideas, using design methods of collaborating and innovating.

IL

Yes, but you can also further the agendas of social research or environmental research by working with the visual, making visual tools. I think that visual tools created by designers are important when we are trying to navigate a really complex set of problems.

MJ

Thinking about design research as the process but also the output is interesting, especially if you come from an academic background where your outcome might more commonly be a report or a written piece. If you make an object which is not a piece of commercial or “useful” design but a piece of speculative or critical design, people are able to use and interact directly with a concept.

CP

So, speculative design is a method to imagine future scenarios that might develop from current societal problems and to design products or services for those scenarios. Critical design goes one step further and makes us question the role that products play in these future worlds. Both aim to spark debate about our potential futures.

MJ

Yes, both the facilitation process and the design outcome open new avenues of research.

Sometimes I think as designers we are guilty of thinking that design can and must solve things, or at least that’s my experience coming from an architecture background.

IL

The purpose of speculative or critical design as a part of design research is not about solutions – designed objects or systems are used to prompt a conversation. This kind of design can nudge a person’s view of something and through doing that, nudge public consciousness. Here, design is not just selling commercial things, but selling new ideas. I feel like that’s really what our contemporary challenges need.

JPP

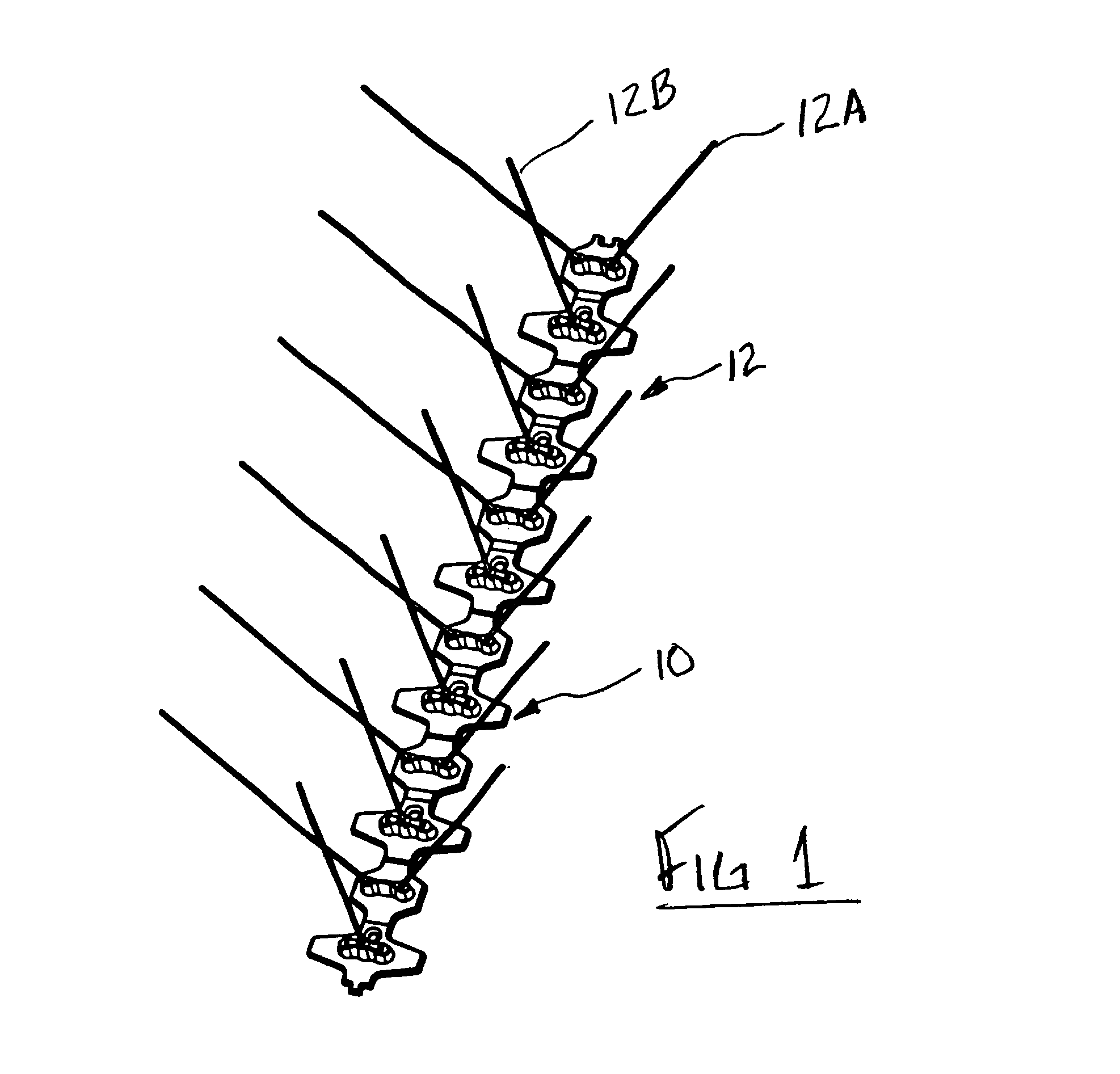

There is also a slightly different take on this: design research as iterative solution-making. And this raises interesting questions, like what exactly are you solving? I think it’s a useful question to ask. If you try to propose a solution to the broken relations between humans and non-human species – being aware of all the problems inherent in trying to solve that problem – it forces you to formulate or define the problem in a different way. It’s a cyclical process, oscillating between problem and solution, back to problem and back to solution. This can be incredibly productive. My work as part of this exhibition will be a kind of prototype that is not a final solution, but part of this ongoing process of design inquiry.

Also, I’ve done projects with scientists or educators, and what they really appreciate from designers is how we generate a narrative as part of our work. Part of generating this narrative is about critically interrogating the context of the research – why have I chosen this inquiry? Why is it important? What does it mean to society? Who tends to fund this kind of research? What are their motives? What are the biases in this area of research?

CP

Rhiarna, design research as critical storytelling is a central theme in your work.

RD

Yes, the research that I’m doing for this residency is about understanding how different forms of narrative allow for different forms of representation; or how particular positions of representation depict different stories or political perspectives. And when I talk about narrative, I speak of forms of representation. A narrative doesn’t have to be verbal or written, it could be images, drawings, mappings, your own or media footage. These narratives are formulated by the knowledges of communities of people, including Indigenous knowledges – the frameworks, the guidelines that a society has to adhere to, its histories and experiences, one’s own life experiences as well.

In my work as part of this residency, I am trying to understand who dictates the narrative on the environmental impacts of deep-sea mining, how that narrative is being funded and how this defines the representation of the subject, and that is inherently a very political act. For me, design research is about becoming aware of the narrative that exists around a topic and then trying to propose new forms of narrative – or maybe it’s not about formulating a new narrative or an output, but giving space to other less-dominant narratives that already exist.

CP

And this bias and particularity of perspective that you mention characterises the story of design itself. When we talk about design and design research, the discipline has a partial and relatively limited set of histories that it uses as its resource. Is this something you address in your work?

MJ

That is definitely an issue that resonates with me and with my project. When researching laundry in the urban setting, it is not necessarily included in architectural history. A large part of the recent history of laundry is placed in the realm of unpaid reproductive labour, which is generally not documented or archived in a way in which paid labour would be. So, my work is about identifying the gaps in documentation and looking at research material that is adjacent to design and architecture histories, such as GLC press releases or tenants associations’ documentation or oral history projects; and then trying to understand these in terms of a history of domestic resource-use.

IL

My own practice of graphic design – versus disciplines like architecture, or even fashion design – has a shorter history of design research, so we lean much more on other disciplines, like social science. And a lot of these tools and frameworks have been co-opted by the commercial sphere to support activities like marketing. I’m interested in how you can take some of these frameworks and tools within graphic design and use them to do good. As well as reclaiming methodologies, my work is about learning from slightly under-explored climate knowledges and visualising these through design, making them more accessible. It’s about giving an audience to the words in particular languages that may not have been centred in conversations about climate. These words hold important meanings that help us to understand the world and climate we inhabit. I think that’s one of the most powerful things about design – it can really communicate ideas to a broader audience.

RD

Leading on from that, there’s a question around what you can situate and understand as a knowledge. Even the academic institutions that we consider reputable sources of knowledge need to be questioned. Certain forms of media or popular culture, or maybe other forms of traditional knowledge that aren’t considered “academic”, are important sources in my work. I think what we consider as forms of knowledge and where we find those could be questioned and decolonised.

JPP

When I founded my collective Feral Partnerships after graduating, one of the first activities that we did was to build up an alternative research archive that foregrounded different kinds of architectural histories that incorporate the non-human. I think when we talk about climate breakdown and biodiversity loss, we could look more at knowledges that exist outside of the recognised human realm – knowledges that aren’t embedded in western industrial and extractive processes. The word “knowledge” is maybe not quite the right word here, it’s a kind of contested term. But certainly a kind of work, activity, agency and aliveness exists outside of what humans do. There are very material consequences to the lack of recognition of those kinds of knowledge.

When I say I’m looking at our relationship with the non-human, it’s important to foreground Indigenous knowledges and Indigenous world views that have that kind of thinking already embedded within them and have established ways to think about these other worlds.

IL

Yes, some of the solutions to climate breakdown and biodiversity probably already exist, but the dominant narratives are maybe not giving us access to these solutions, and that’s why research projects like James’ are so important.

JPP

There is a kind of commonality across all our projects – we are looking at the hidden mechanisms or hidden worlds that are critical to supporting all of our lives.

CP

But as you disclose the weaknesses of the systems you are studying and operating within, you’re faced with a daunting question: what agency does the designer or design researcher have to change these faulty, biased or outmoded systems, many of which underpin our current climate emergency? What impact do you hope your work will have?

MJ

As a group, we’ve had conversations about the scope for impact in our projects. We all have varying perspectives on what we think we can achieve. But at this moment in our practices, where we are starting to identify the social, political and environmental systems we live in, the hope is that people who encounter our work will recognise that those systems are purposefully designed, rather than something that occurred naturally.

CP

Yes, with the implication being that that they can be redesigned.

RD

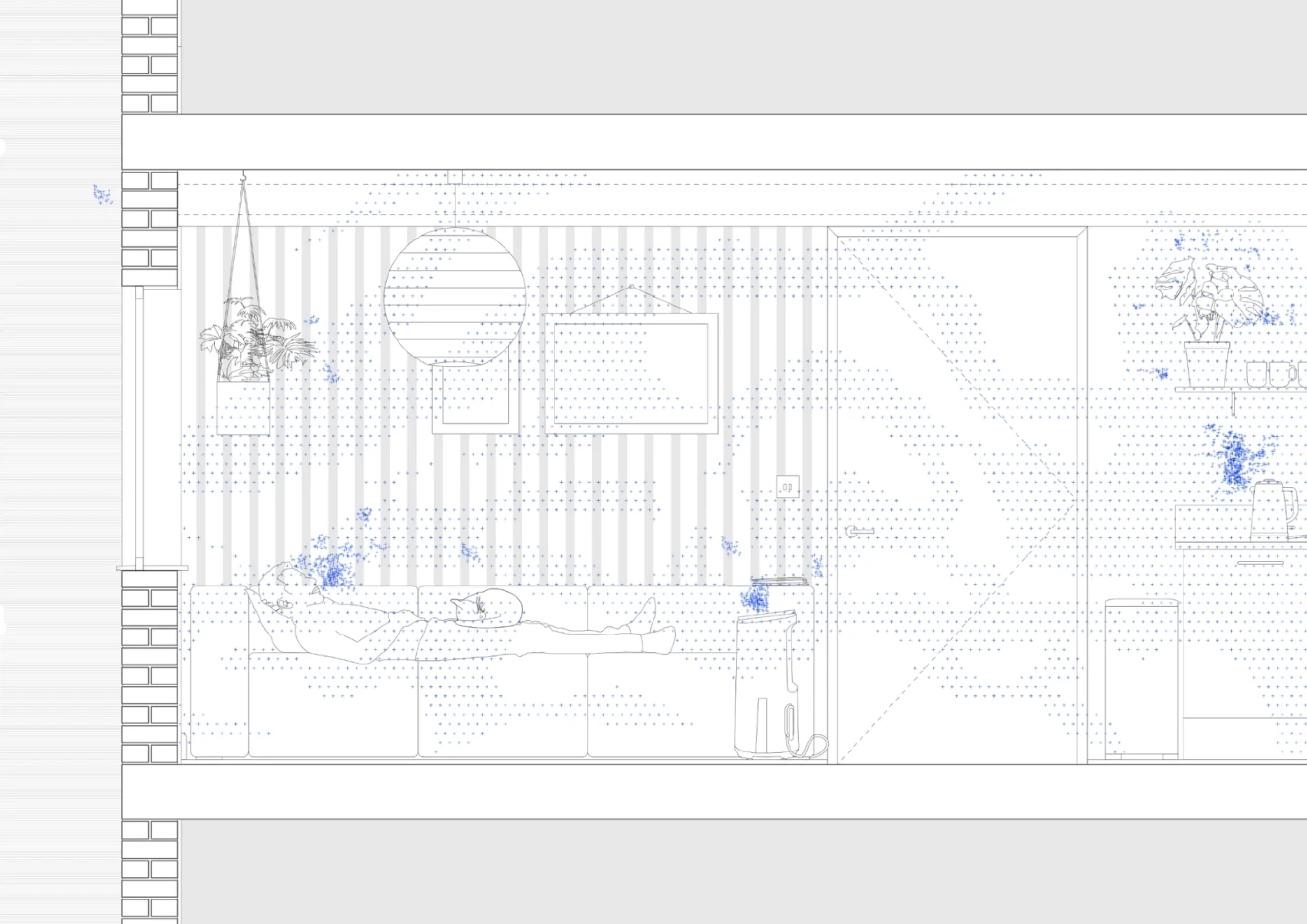

In my case I’m dealing with systems related to geopolitical ecological impact, and I don’t have influence in the same way as a policy maker or a lawyer or ecologist. As a design researcher you need to reckon with your own agency. But design researchers can produce research outputs that are more visual or aesthetic than language-based outputs. And visual output, especially when it is exhibited in a public arts institution like this, is a very influential, important and powerful form of research.

Having a background in spatial design and architecture, I am accustomed to questioning how we live and what spaces and places look like – and how these might change in the future. As designers, we have the potential to speculate on potential futures and to visualise them for others. Speculation itself could be seen as a potential output of design research.

IL

Yes, it’s important to use the Design Museum’s platform to show people what a design output can be and what design can do, and to show the process of design research. Showing our research process to a Design Museum audience invites more people to understand the value of design research. This is an impact itself.

CP

So in summary, design research does not necessarily propose solutions, but redefines the problem, reframes the questions or perhaps sets out a creative brief for new systems to come.

IL

Design research is about reimagining how we relate to the world, but also helping other people reimagine how they relate to the world.

JPP

I think there’s a growing understanding that most of the answers to our environmental, social or political problems are probably not about making more things – we have a lot of designed things in the world already. It’s about designing new ways of thinking.

Design Researchers in Residence: Islands opens at the Design Museum on 23 June 2023 and runs until 24 September 2023. Entry is free and no booking is required.